Dr Nial Moores, Birds Korea, April 2nd 2023.

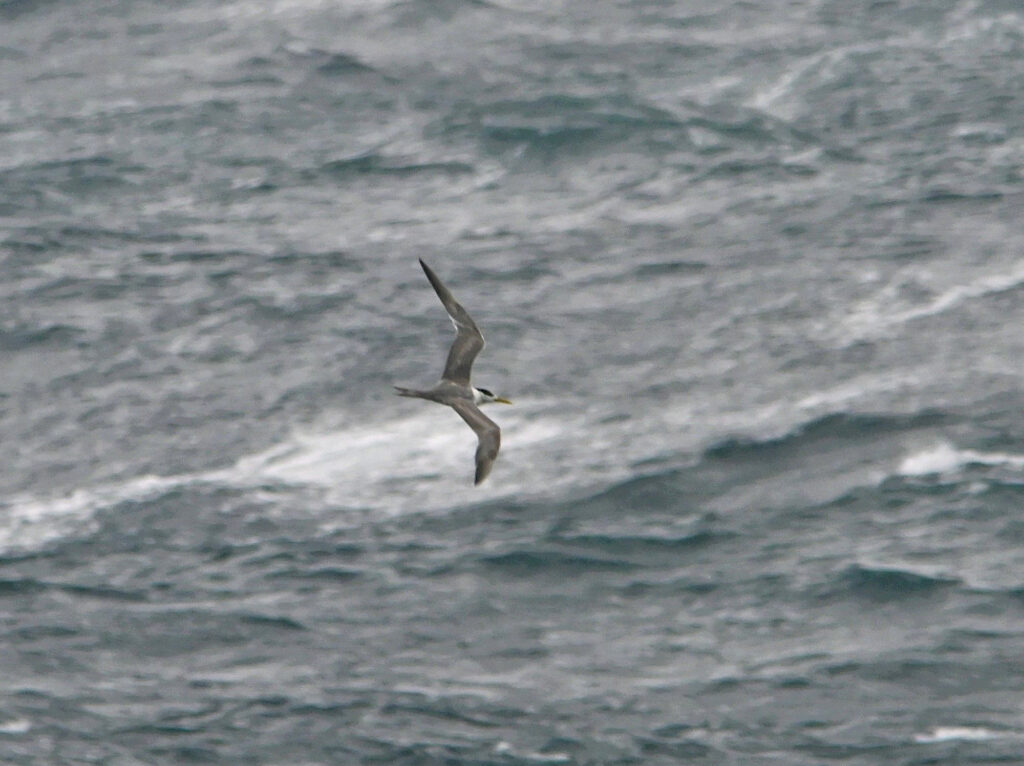

The Critically Endangered Chinese Crested Tern Thalasseus bernsteini 뿔제비갈매기 is a strikingly pale and rather slender seabird, a little smaller than a Black-tailed Gull Larus crassirostris, with a long, orange-yellow black-tipped dagger of a bill. In breeding plumage, adults have glossy black caps, reaching from the bill base back to a luxuriant spiked crest; non-breeding adults and juveniles have white crowns, with a black spot before the eye and a rather shaggier looking mane.

Confined to the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), the species is both one of the world’s rarest migratory birds and the rarest species globally to be found annually in the Republic of Korea (ROK).

Following several decades without adequately documented records anywhere in the world, the species was re-discovered in 2000. Between then and 2012, the global population was estimated to be fewer than 50 individuals. It has taken years of intensive conservation efforts, largely initiated in 2013, to help the population start to recover, with the species increasing to as many as 150 or even 200 individuals by late 2022 (EAAFP 2023a). The 1% of population threshold remains as one bird (Wetlands International 2023): i.e., any site that supports one or more Chinese Crested Tern, for five years or more, meets Ramsar Convention criteria for identification as being an internationally important site.

Records suggest that the Chinese Crested Tern winters largely in Eastern Indonesia and the Philippines and nests only on uninhabited islands in the East China Sea and in the Yellow Sea (EAAFP 2023b). As a species that nests on the ground, in among large numbers of other terns or gulls, the species is extremely sensitive to disturbance when nesting. One of the most important and successful conservation actions has therefore been to enforce strict access restrictions to nesting islands during the breeding season, both to reduce disturbance (including e.g., by birders and recreational anglers) and also to prevent taking of eggs for food. To an apparently lesser extent, the species can also be vulnerable to disturbance when roosting and feeding.

Considering the Chinese Crested Tern’s extreme rarity, special care is therefore needed at all times and at all sites to avoid flushing or disturbing the species.

On the Korean Peninsula, the first record of Chinese Crested Tern was one collected on an island on July 5th 1917, “72 miles north of Chemulpo” (in Austin 1948), an old name for Incheon. Although misidentified at that time by the Japanese ornithologist Kuroda as Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergi, his description clearly identifies this individual as Chinese Crested (Simba Chan in lit.), as long suspected by Birds Korea. Although the exact location has not been traced, the bird was presumably collected on a small island off the Hwanghaenam coast in present-day DPR Korea. It seems likely that the species was breeding there. This assumption is based on dates of breeding from more recent research conducted following the (sensational!) discovery of nesting Chinese Crested Tern on a small island in Yeonggwang County, ROK, on April 28th, 2016 (Song et al. 2017); and the 21 which were collected off from the Shandong Peninsula, PR China, only 200-300 km to the west of Incheon, in 1937 (EAAFP 2023b). This was the largest known concentration of records anywhere in the world before the present century, leading Liu et al. (2009) to assume that there was a breeding population there, at least in the 1930s.

In the ROK, the Chinese Crested Tern is now an annual visitor between March and August in tiny numbers (still just below the 10-a-year threshold set by Birds Korea for recognition as a “regularly occurring” species).

All confirmed records to date come from Yuksan Island in Yeonggwang County, 6-7 km off from coast, and the adjacent mainland coastline, north to Gochang County (a stretch of ~10 km of beach and tidal flat, in between very extensive tidal flats at Baeksu to the south and Gomso Bay to the north, totalling several thousand hectares), both within Jeollanam and Jeollabuk provinces in the southwest of the country. Based on an islander’s personal account, however, one was also likely present on Baengnyeong Island (Incheon) at the edge of a large nesting colony of Black-tailed Gulls in at least April 2013 and 2014. He described the bird as “white with a black head and a long knife-like orange bill” which “made a noisy shrieking sound and dived into the water to catch fish”. Unfortunately, we failed to re-find the bird during multiple-hour stays at the same location; and although I have little doubt that he was describing a species of tern, it is not possible to rule out other species (see below).

According to Lee et al. (2021), the number of Chinese Crested Tern seen on Yuksan Island increased from five in 2016 to eight in 2020. The terns arrive at the breeding site in pairs (or sometimes alone) and asynchronously. The first individuals were observed on March 29th, 2018; March 30th, 2019; and March 21st, 2020, only staying on the island during the night until eggs were laid. The first eggs were recorded on April 18th in 2018 and 2019, and on April 19th in 2020. One pair during 2019-2020 and two pairs during 2016-2018 attempted breeding. During the five years, a total of 11 active nests were found, including second brood replacement eggs, but chicks successfully fledged from only four of these. Clutch size was one (n=11), and the incubation period was 26-28 days. The chicks flew with the parents 37 to 43 days after hatching.

The national Ministry of Environment (MOEK 2022) stated that seven Chinese Crested Tern visited Yuksan Island in 2022; one pair nested; and one young was fledged. The seven included an adult which had been banded on the island in 2021, suggesting site fidelity. The same adult, which apparently did not breed in 2022, was banded again (this time with a white band, marked with the letters “PA”), as was a breeding female (white band, “PB”) and 2022’s only chick (light blue band, with the numbers “070”).

Re-sighting of these marked birds helped confirm seasonal movements of these birds away from the nesting island. In 2022, PA and 070 were seen and photographed along the Gochang coast on August 2nd (MOEK 2022), and on 5th 070 was photographed beautifully by Dr Sung Sooyoung, together with an unmarked Chinese Crested Tern from Yuksan Island. No Chinese Crested Terns were seen on August 6th or subsequently in 2022.

Both PA and PB were then resighted soon after (perhaps the next day, on August 6th) in Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao, on the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula, >500 km WNW of Gochang. In addition, a bird which was colour-banded as a chick on Yuksan Island in 2021 was seen in September 2021 near to Shandong; and in 2022 was then seen on June 21st in Yilin City Taiwan and in August in Jiaozhou Bay (MOEK 2022; EAAFP 2022).

Jiaozhou Bay in Qingdao is now recognized as an exceptionally important post-breeding congregation site for the species from August to October, with birds presumed to fly north from Chinese breeding colonies (as evidenced by one bird carrying a satellite transmitter) in addition to birds from Korea. Seventy-two were recorded in Qingdao on October 5th 2021, and at least 82 birds were seen there in August 2022 (EAAFP 2022). In addition, Chinese Crested Terns have also been seen several times north of the Shandong Peninsula, in the Bohai (northern part of the Yellow Sea).

In 2023, ROK records of Chinese Crested Tern known to us at this time include one breeding plumaged adult seen along the Gochang coast on March 21st (reported on eBird, with supporting images); 2-3 birds in breeding plumage which I saw and digiscoped along more or less the same stretch of beach on March 27th; two seen and photographed on March 30th; and two or more seen on April 1st, including the banded bird PA.

On March 27th, one was ‘scoped distantly, and apparently flew off within minutes. This sighting was followed an hour later by two together, sleeping (with bills tucked into back feathers) or walking along the water’s edge 2 km to the south (so either two or three individuals in total). Neither of the better-seen birds had leg bands; both were in breeding plumage but one (Bird A) showed plain grey primaries, while the other (Bird B) showed some darker barring on the primaries, a faintly darker bar across the secondaries, and some darker streaks on the upperwing coverts, visible when the bird stretched and in flight. As the tide came back in, Bird A and B had to keep shifting position, taking flight twice before landing back down, with Bird A calling several times in flight (a long “Keeeyikk”), and briefly initiating display, with wings drooped and head raised and thrown back. Bird B did not respond. Bird A soon after flew out to sea; Bird B remained another 30 minutes, sleeping or walking to escape the tide (fortunately for me, coming closer and closer, as we both ended up standing in the water).

Slow motion video of Bird B, March 27th 2023 © Nial Moores, showing faintly darker markings on the secondaries (the deep sound is a slowed-down Black-tailed Gull!)

Expert opinion is being sought to determine whether these darker markings and the barring on the primaries indicate immaturity or not. At least some literature suggests that larger terns tend to first breed at three years or older; with birds in their second calendar year not returning to natal areas. Perhaps birds with trace markings like these are in their third or fourth calendar-year?

Identification from similar species

The Chinese Crested Tern is strikingly pale in all plumages, and has a long and strongly-coloured bill. Confusion (even at long range) is therefore unlikely at any age with any gull or e.g., with the much smaller Little Tern Sternula albifrons, which has a very different fluttering flight action and also a different head pattern. Confusion is perhaps possible, however, with three other large tern species: Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia 붉은부리큰제비갈매기, Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergi 큰제비갈매기 and Lesser Crested Tern Thalasseus bengalensis, the latter species as yet unrecorded in Korea.

The Caspian Tern 붉은부리큰제비갈매기 is a rare non-breeding migrant to the ROK. First recorded here in 2001, there are now several records a year, including of birds over-wintering on Jeju and in the Nakdong Estuary. The species appears to be more widespread in the DPRK, and is locally very common along parts of the Chinese coast. Both when on the ground and in flight, the Caspian Tern looks substantially bulkier and more thickset than Chinese Crested and in many ways more gull-like than tern-like. Caspian also has slightly darker grey on the upperparts and a very heavy and deep red bill, often with a darker tip. Caspian also shows extensive dark on the underside of the primaries, visible even at long range.

The Chinese Crested Tern’s closest relative in this region and a more likely confusion species in Korean waters is Greater Crested Tern 큰제비갈매기. An expert account on the EAAFP website states that “the Greater Crested Tern breeding along the coasts of Zhejiang, Fujian, Taiwan and Guangdong are likely belonged (sic) to one population that migrates to Indo-china, Thailand, Myanmar and the northern Philippines. This population is probably around 30,000 birds with an increasing trend.” The Greater Crested Tern also nests locally in southernmost Japan, with birds dispersing north in small numbers to the Kyushu coast (and islands offshore from there), and east to Tokyo Bay.

The Greater Crested Tern 큰제비갈매기 is primarily a species of warm oceanic waters in the tropics and subtropics. As such the species remains rare in Korean waters. The first record was of a flock off from Jeju Island on June 26th 2011, with the five or more subsequent records including 2-3 seen from Busan (with the first of these on August 1st 2012) and at least three seen along the east coast, with one photographed in Sokcho in mid-February 2020 (posted by Jina Yi on eBird) and two photographed flying past the Guryongpo Peninsula on September 6th 2020.

Compared to Chinese Crested Tern, Greater Crested Terns seen in this region are heavier-looking, and have much darker grey upperparts, including the rump and tail and upperwings, often with irregular-looking contrasts. Greater Crested also has an unmarked, rather drooping yellowish bill, sometimes with greenish tones (a banana rather than a carrot for a bill…).

In several respects, Chinese Crested Tern recalls Lesser Crested Tern more closely than Greater Crested. However, Lesser Crested also lacks a dark tip to the bill; is slightly darker grey above and shows more obvious greyer tones to the rump and tail. Lesser Crested, like Greater Crested, is also a species of warm oceans in the tropics and subtropics. It has therefore yet to be recorded in Korea, and remains genuinely rare in East Asia – though according to eBird has been recorded as far north as the Bohai in the Yellow Sea.

Closing Thoughts

Based on the pattern of records (both historical and contemporary) it is tempting to consider the Chinese Crested Tern as primarily a Yellow Sea specialist, which became separated ecologically from the Greater Crested Tern presumably because of its stronger tolerance of seasonally colder and perhaps more turbid waters. This assumption finds some support in two additional strands of evidence.

The first is that mixed pairs of Greater Crested x Chinese Crested Tern have been observed in more southern colonies, producing a small number of hybrids (if these two species long overlapped “naturally” it seems a little difficult to see how Chinese Crested Tern would not have already been genetically overwhelmed by the much more numerous Greater Crested).

The second is that conditions provided by the Yellow Sea (now as in earlier epochs) support speciation. The Yellow Sea has long been fed by rivers that drain much of the East Asian landmass. The sea also experiences some of the strongest tides in the world. This has helped to create patches of exceptional natural productivity, both in estuaries and along tidal fronts that can be used by foraging seabirds. The present morphology of the Yellow Sea, as in the past, also includes several thousand islands, including those created by sea-level rise 10,000 years before present. There is therefore an abundance of potential sites available for nesting birds in the Yellow Sea which, especially before the large-scale arrival of people (and rats and feral cats), were too small and likely too cold in winter to be able to sustain populations of larger land-based predators. As a result of the Yellow Sea’s exceptional conditions, several highly specialised shorebirds depend on the Yellow Sea during migration (including the Critically Endangered Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmaea) and at least a half-dozen globally threatened and near-threatened breeding bird species have their centre of abundance fixed firmly in the Yellow Sea, with only small outlying populations: Far Eastern Oystercatcher Haematopus (ostralegus) osculans (NT), Saunders’s Gull Chroicocephalus saundersi (VU), Swinhoe’s Storm Petrel Oceanodroma monorhis (NT), Black-faced Spoonbill (EN), Chinese Egret (VU) and Styan’s Grasshopper Warbler Helopsaltes pleskei (VU). The last four of these are complete seasonal migrants which breed almost exclusively on offshore islands, while one of the six (Far Eastern Oystercatcher) nests on islands and along the shore. Perhaps predictably, in the ROK at least three and probably four of these species also nest in the same island group as the Chinese Crested Terns; and Far Eastern Oystercatcher, Black-faced Spoonbill and Chinese Egret also share the same tidal flats and beaches which Chinese Crested Terns use for loafing in March and again in late July / early August.

Either way, for whatever reason, Greater Crested Tern did not colonise the Yellow Sea; but Chinese Crested Tern did. And remarkably, in spite of the seasonally much colder sea and air temperatures in early spring, Chinese Crested Terns which nest in the ROK choose to breed substantially earlier than those breeding further south. They are also willing (perhaps reluctantly?) to nest in among hordes of Black-tailed Gulls, a rather larger and heavier species – perhaps because of the lack of other terns.

More northerly nesting can provide terns with multiple advantages, however. Egg-laying and incubation in April and May allows Chinese Crested Terns in the ROK to avoid the worst impacts of the rainy season when on the nest; and fledging in July (with movement west / northwest to the Shandong) also enables birds to avoid being impacted by the vast majority of early typhoons. In addition, they are free from competition from any other tern species, as the only breeding tern in the Korean part of the Yellow Sea is the Little Tern, which is confined to inshore marine waters and freshwater habitats.

If they are primarily Yellow Sea specialists, then why have so few been found nesting in Korea and why were none found nesting along the Shandong Peninsula in 2006? In addition to historically heavy predation of bird eggs by people in PR China and Korea for food, it also seems possible that – like the Black-faced Spoonbill – the Chinese Crested Tern might have suffered from exceptional levels of disturbance in the 1950s during the Korean War followed by decades of increased levels of egg-harvesting post-war due to very poor levels of human food security. Those terns that still tried to nest in the Yellow Sea would therefore likely have done so in areas that are largely inaccessible – and therefore likely not surveyed. Even now, many islands in the ROK have either never been surveyed or have been surveyed only quickly or infrequently; and even islands along the Hwanghaenam coast in the DPRK, where the first Korean record was made, have for decades been off limits to researchers.

Maybe none survived, but a dozen pairs or so of nesting Chinese Crested Terns in the Yellow Sea could easily have been over-looked, scattered across several islands. Lacking a large population, there would be no pull to concentrate birds or to form a large “pure” colony; and remaining undiscovered by conservationists would also mean that no conservation measures will have been taken to remove invasive rats or to reduce casual disturbance, helping to keep the population low. In contrast, as opportunistic colonists, the few individuals which did choose to nest in the very south of their breeding range have been able to benefit enormously from recent conservation actions – allowing their known population to increase from 50 to 200 in only a decade (even though hybridisation with Greater Crested Tern now poses a threat).

There is so much still to learn about and to do for the Chinese Crested Tern – perhaps especially in the Yellow Sea. In addition to conservation measures on the nesting island itself, there is an urgent need to ensure protection of their “spatial requirements”. It would therefore seem highly appropriate to include the whole area used by Chinese Crested Tern (the nesting islands, marine inshore waters, tidal flats and beaches – a total area of c. 50,000 ha) within Phase 2 of the World Heritage Listing of Korean Getbol (Tidal Flat).

At the very least, thanks to the researchers who discovered nesting islands in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea; and the conservationists and governments who have already taken decisive actions to protect them (including the Ministry of Environment here in the ROK); and thanks of course due to the plucky survivalist instincts of the terns themselves, the spectacular Chinese Crested Tern now, finally, has a fighting chance to recover in number.

Acknowledgements

My sincerest thanks to Dr Sung Soyoung who so generously shared his amazing images of Chinese Crested Tern for this blogpost; Professor Amael Borzee, for sharing his images of Greater Crested Tern with Birds Korea; and to “prefer-to-remain-anonymous” for driving me around the site! Thank you!

References

Austin. 1948. The Birds of Korea. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. Vol. 101, No. 1.

EAAFP. 2022. Chinese Crested Tern banded in Republic of Korea sighted in China. EAAFP website, posted on August 24th 2022 and accessed in March 2023 at: https://www.eaaflyway.net/rok-banded-cct-sighted-in-china/

EAAFP. 2023a. Special achievement award to the Chinese Crested Tern team. EAAFP website, posted on February 27th 2023 and accessed in March 2023 at: https://www.eaaflyway.net/award-to-the-chinese-crested-tern-team/

EAAFP. 2023b. Chinese Crested Tern. Accessed in March 2023 at: https://www.eaaflyway.net/Chinese-crested-tern/

Lee, Y-K., Kim W-Y., Kang J., Yoo S-Y., Cha H-G., Lee S-Y. & No D. 2021. Arrival and breeding status of the Chinese Crested Tern (Thalasseus bernsteini) in Korea. Korean J. Ornithol. 28(2): 66-74 (2021).

Liu Y., Guo D-S., Qiao Y-L., Zhang E. & Cai B. 2009. Regional Extirpation of the Critically Endangered Chinese Crested Tern (Thalasseus bernsteini ) from the Shandong Coast, China? Waterbirds, 32(4):597-599 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1675/063.032.0414

Ministry of Environment (ROK). 2022. The Ministry of Environment identified the migratory routes of the Chinese Crested Terns. Press Release, September 16th 2022. Accessed in March 2023 at Korea.Net: 220913-신비의 철새 뿔제비갈매기, 이동경로 밝혀졌다.

Song S-K., Lee S. W., Lee K. Y., Lee . Y., Kim C. H., Choi S. S., Shin H. C., Park J. Y., Lee J. H. & Kim W-Y. First report and breeding record of the Chinese Crested Tern Thalasseus bernsteini on the Korean Peninsula. Short communications. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 10 (2017) 250-253.

Wetlands International. 2023. “Waterbird Populations Portal”. Retrieved from wpp.wetlands.org on Thu Mar 30 2023.